MRIs and a connection to tackling some of life’s obstacles

In this blog post, I’ll weave one of my typical stories that will begin with my enthusiasm and excitement for MRIs, again with a series of numbered citations for those interested in further reading. The timing of this post is connected to me recently having my 13th MRI, on Friday September 13, 2024, where my enthusiasm overflowed for a few reasons. In this post I will explain my excitement about MRIs, link back to a challenging MRI experience, then will use my own approach to handling that challenge and subsequent ones to build on the ways we can all approach life’s obstacles and challenges and include some references along the way. In talking about challenges, I might touch on topics that make you consider the obstacles or challenges in your own life, so please, take care while reading. If it sounds interesting though, please read on!

My first MRI took place on October 13th

2022, nine months after my initial appointments with family doctor,

psychiatrist and neurologist in January 2022; I WAS EXCITED! My interest in medical imaging began in high

school. For a school project, I visited

our local hospital to learn and report on the technologies in use there in the

early 1990s. In University, I added a

Physics minor to my Biochemistry major and knew both the underlying physics and

application of theory that went into creating these amazing machines. I had a workable understanding of how MRI

scanners work: a STRONG magnetic field lines up protons in hydrogen

nuclei along the common axis of the MRI scanner bore, then specifically tuned

radio frequency pulses deflect the protons’ magnetic vectors such that the

protons in different tissues and micro-environments resonate differently and

receiver coils in the scanner detect that resonance at different

frequencies, while measuring the time it takes for the magnetic vector of those

deflected protons to relax back to the aligned axis (the T1 relaxation time)

and for the axial spin to relax back (the T2 relaxation time).

A commonly used 1.5 Tesla scanner has a

magnetic field strength of about 15,000 Gauss (roughly 30,000 times the

strength of the Earth’s ~0.5 Gauss field) which already is impressive to

me. When I think about the controls

needed to maintain the primary magnetic field then manipulate the X/Y/Z

gradient coils, shim coils and radiofrequency coils, computing power required

to produce each tissue-focused pulse sequences, and the sheer computing power

needed to collect data for relaxation times measured in milliseconds (thousands

of a second) then to compile and analyze that data so that the imaging

calculations can produce the typical ‘slice’ images we’re familiar with. In these two paragraphs, I’ve covered and

added bold text to the magnetic, resonance and imaging

components that give an MRI its name. It

still fascinates me that we’re able to use physics and engineering to get these

unique images of our bodies with non-invasive techniques that use safer radio

frequencies instead of more energetic x-rays

Obstacle 1: Panic

how I felt while listening to them. I found the “MRI Scan Sounds Explained…” video by MRIPETCTSOURCE (https://youtu.be/Pxw2ZpGp5AM?si=FoSEC5OuQh-4DET9) to be very helpful, and quickly learned that just hearing the sounds at a low volume left me feeling uneasy. I began my own home-grown model of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

Before I go further in explaining how I’ve

used similar approaches, I want to point out that in each of these, I used

earbuds / headphones as my chosen technique, and I did so on my own – without guidance

from a professional – but not without stopping to carefully assess and consider

the chance of unintended consequences or harm.

I considered my approach to be low risk, as I could at any point stop

the audio or take out the earbuds / remove the headphones. I’ll soon speak more about why I’m not

suggesting everyone should try their own ‘at-home CBT handy-project’, rather I’m

sharing as some ideas about how we can prepare for how we face obstacles ahead

of us.

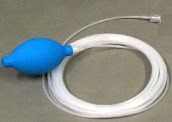

For my foot, I knew I needed more help, so I

chose a professionally-guided approach with physiotherapy and exercise. I benefited from instructions from my physiotherapist

on useful stretches and use of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

(TENS)

Obstacle 2: Language

Early in my recovery, I faced several

obstacles from my newly renovated brain.

I began referring to it / me as ‘Stu 2.0’, which soon merged from ‘Stu two.0’

to ‘S_two.0’ or ‘Stu.0’, where I quickly learned that I had near-zero real-time

memory and was unable to remember any events from a day, which was made worse

by anything that added vibration to the fluid that remained in my resection

site, such that vibration from travel would nearly assure that I wouldn’t

remember anything from a given day. I found

myself much more ‘on edge’ or ‘jumpy’, which with my care team we later suggested

was because of local brain structure renovations in Stu.0 where the surgery

left my amygdala intact but renovated its surroundings. The amygdala is located at the underside of

the temporal lobe from where it regulates our ‘fight or flight’ response that

links to emotional reactivity and associative learning and other cognitive

processes.

By writing a daily journal and studying it

later, I was able to begin remembering by retraining Stu.0 for a new way of memory

consolidation through focused and purpose-built personal distributed learning

While Stu.0’s ability to hear was not, my ability to

detect and understand language was, particularly when language was coming from

my right side and in environments with other background noise. This was easy to understand by reviewing that

the temporal lobe is responsible for: memory, learning, controlling emotions,

speech, and language.

While Stu.0’s ability to hear was not, my ability to

detect and understand language was, particularly when language was coming from

my right side and in environments with other background noise. This was easy to understand by reviewing that

the temporal lobe is responsible for: memory, learning, controlling emotions,

speech, and language.

I’m now back to being able to detect

language in my surroundings, such that I don’t need to pay much attention to

where conversation would originate in my environment. I consider this to be a success in navigating

around my language obstacle, by re-training Stu.0 in recognizing voices,

likely by creating new neural pathways that successfully navigated around the

resected portion of my right temporal lobe.

My latest obstacle: Music

I’ve been doing remarkably well as I

approach my two-year ‘cranioversary’ but have noticed new internal experiential

changes that that I’ve only been recently able to connect to some external stimulus,

and I’m better able now to understand that music has become a negative trigger

for me. My newest obstacle comes in the

form of strong unease in some environments featuring music in the background. My response has ranged from panic to terror, which

I see as an explanation for why I’ve not yet been able to make a strong link to

exactly what it is that is causing this new response, but it seems to be linked

to a group of musical phrases and cadences, specific notes, or tempo. With the temporal lobe’s “[involvement] in

short-term memory, speech, musical rhythm and some degree of smell

recognition”

This is something that I want to solve, so

I’m back to my now familiar trick of using earbuds and headphones to try to

retrain my brain around its new behaviour. I’m finding songs that trigger my panic /

terror response more strongly and am listening to them first at low volume then

increasing the volume and moving to the richer sound of better-quality

headphones. Again, I see this as a low

risk home-baked CBT approach where I can easily turn the volume down or stop if

I feel overwhelmed. It’s my caution /

disclaimer to ‘not try this at home’ for other obstacles, but one that for me I

have hope will be able to help me enjoy music again.

Connecting the puzzle and reintroducing hope

In telling this story, I connect it back to

the obstacles we ALL face in our own lives.

We each travel with obstacles and fears that don’t show on the surface

and where I hope we can show compassion to others as we all face our own

day-to-day.

I’ve linked a few small ideas about getting

through our obstacles by finding ways to minimize them and making them

easier to face or getting around them by taking different routes or

retraining ourselves for new ways of approaching things. The way I’m describing it is fuzzy, but I

hope I’ve given you some food for thought here.

When we identify the challenges ahead of us, we can take our own approaches

to get through or around them, AND we can engage the help of professionals who

have strong tools to assist us, or our friends and networks who can be there to

support us as we face our obstacles in hope of a better tomorrow.

With that, I hope you take care of yourself

as you face your own challenges, show compassion for yourself to allow space to

try as many attempts as you need to succeed – sometimes referred to as the Frequent

Attempts In Learning approach – and

for others because we never know what challenges others are facing. I wish you well, and please wish me luck in

my next ‘navigating around’ project!

A small update, a few days later...

Works Cited

1. How does it work?: Magnetic resonance imaging. Berger,

Abi. 7328, 2002, BMJ, Vol. 324, pp. 35-35. https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/pmc1121941

2. Elert, Glenn. Electromagnetic Spectrum, The

Physics Hypertextbook. hypertextbook.com. [Online] [Cited: 19 9 2024.] http://physics.info/em-spectrum/.

3. Strengths-based cognitive-behavioural therapy: a

four-step model to build resilience. Padesky, Christine A. and Mooney,

Kathleen A. 4, 2012, Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, Vol. 19, pp.

283-290. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/cpp.1795

4. Cleveland Clinic. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve

Stimulation (TENS). Cleveland Clinic. [Online] 25 09 2023.

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/15840-transcutaneous-electrical-nerve-stimulation-tens.

5. Physiopedia. Neuromuscular and Muscular Electrical

Stimulation (NMES). Physiopedia. [Online] [Cited: 19 09 2024.]

https://www.physio-pedia.com/Neuromuscular_and_Muscular_Electrical_Stimulation_(NMES).

6. The amygdala and emotion. Gallagher, Michela

and Chiba, Andrea A. 2, 1996, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, Vol. 6, pp.

221-227. https://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8725964

7. Distributed learning enhances relational memory

consolidation. Litman, Leib and Davachi, Lila. 9, 2008, Learning

& Memory, Vol. 15, pp. 711-716. http://learnmem.cshlp.org/content/15/9/711.full.html

8. The Brain Tumour Charity. The human brain. The

Brain Tumour Charity. [Online] 2024. [Cited: 19 September 2024.]

https://www.thebraintumourcharity.org/brain-tumour-diagnosis-treatment/how-brain-tumours-are-diagnosed/brain-tumour-biology/the-human-brain/#h-temporal-lobe-nbsp.

9. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Brain Anatomy and How the

Brain Works. hopkinsmedicine.org. [Online] [Cited: 19 09 2024.]

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/anatomy-of-the-brain.

10. Cellular mechanisms of neuromodulation in a small

neural network. Harris-Warrick, Ronald M. 2011, The Biomedical

& Life Sciences Collection. https://hstalks.com/t/1959/cellular-mechanisms-of-neuromodulation-in-a-small-

Comments

Post a Comment